There is a myth in ecommerce land that DTC (direct-to-consumer) is good for the consumer and good for the brands too.

Here is the thinking: DTC helps brands make more money because they are cutting out middlemen (distributors and retailers), and consumers win because they are getting better quality at a better price.

Sadly, the data does not bear that out.

As it turns out, the DTC model often costs brands more money to get a DTC product into the hands of consumers, and as a result, consumers are paying more for less.

I am going to walk through the numbers and compare the two models. In the end, you will see why I conclude that DTC may not be the best approach for all brands. In fact, in some cases, it should not even be on the table at all.

True Gross Margin (A Measurement of Efficiency)

Before we can really compare traditional distribution models to DTC, we need a way to compare apples to apples. To do that, I want to introduce a term that I will call true gross margin.

True gross margin is simply the total margin that exists between the consumer price and the brand’s COGS (cost of goods).

In a DTC model, true gross margin is just gross margin. If a product costs $20 and you sell it for $100, the gross margin is $80 or 80%.

In traditional distribution, true gross margin is essentially the same thing, but there are different entities (middlemen) collecting some of that margin. With the same $100 retail product, in a traditional distribution model, perhaps $40 is going to a retailer and $20 is going to the distributor.

But, regardless of how the gross margin is distributed, the true gross margin is still 80% and is still calculated by subtracting COGS from the final retail price and dividing by the final retail price ($100 Retail – $20 COGS) / $100 Retail).

Now that we have created this apples-to-apples comparison, here is something I would further say about true gross margin: it is a test of the efficiency of the distribution model.

Let’s illustrate it this way: consider a brand that makes a product for $20 and generates a 10% net profit. If that profit can be achieved with a low final retail price of $40, the distribution model is very efficient; on the other hand, if the final retail price has to be $100 to get that 15% net, the distribution model is far less efficient.

Brands win by getting products sold efficiently. If distribution is inefficient, the retail price goes up and competition becomes difficult. Consumers also win with efficient distribution because they end up paying less.

Note: When I use the word distribution in this context, you could switch out the term marketing. In traditional distribution, a lot of the marketing responsibility falls on the middlemen (distributors/retailers) while in DTC, the brand takes on the marketing responsibility. Just to keep things on an apples-to-apples comparison model, I am sticking with the term distribution.

The important thing to understand is that I am referring to the process of actually getting products sold once they are made.

Comparing DTC to Traditional Distribution

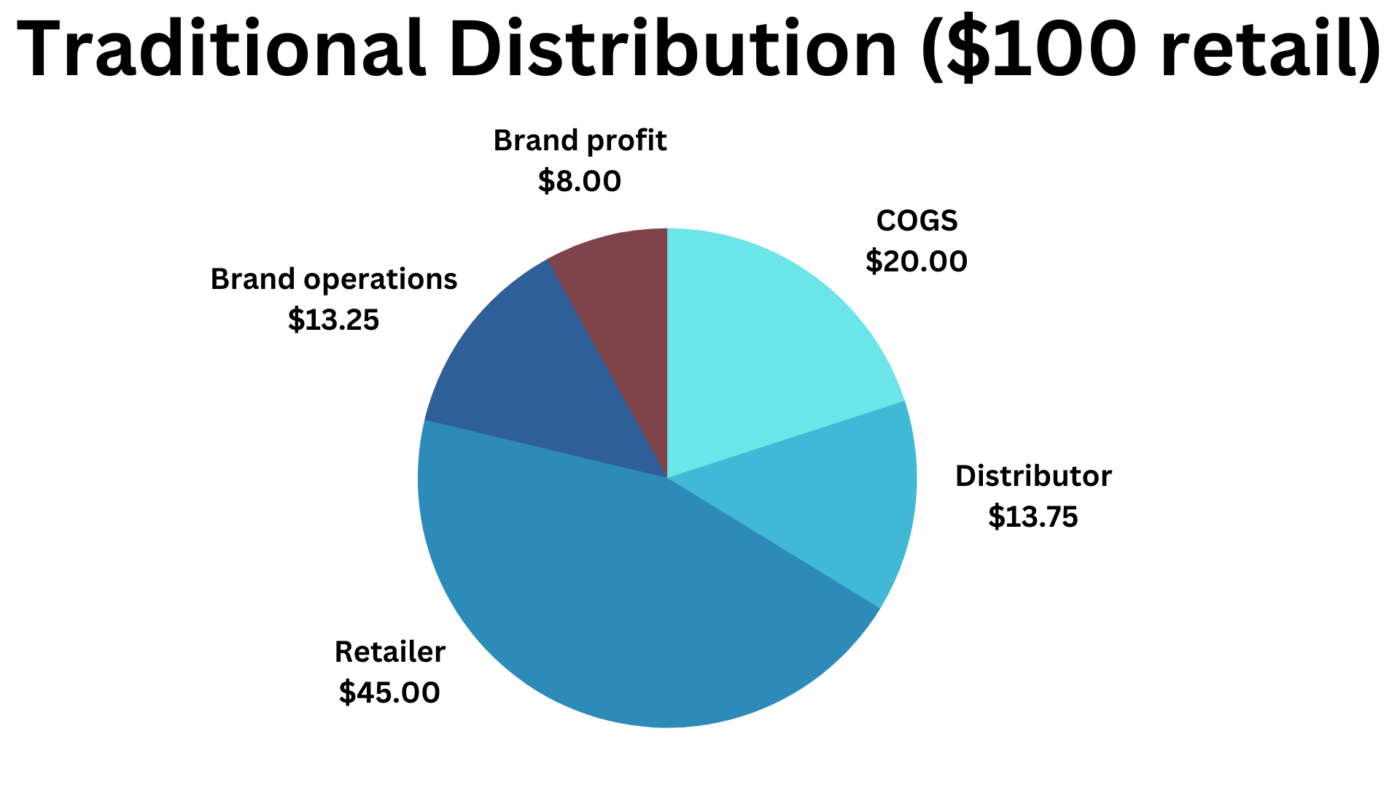

Obviously, situations and numbers vary by industry, but in general, the three players in traditional distribution are the brand/manufacturer, the distributor, and the retailer.

Typically, the retailer is working with a gross profit of 45%, the distributor is operating on a gross profit around 25% and the brand is operating on a gross margin of around 50%.

Here is how the breakdown might look if COGS is $20 and the final retail price is $100:

Now, let’s talk about DTC. If a product has $20 COGS and is distributed DTC without distributors/retailers, you might be tempted to think that the brand can just mark up 100% and sell the product at $40.

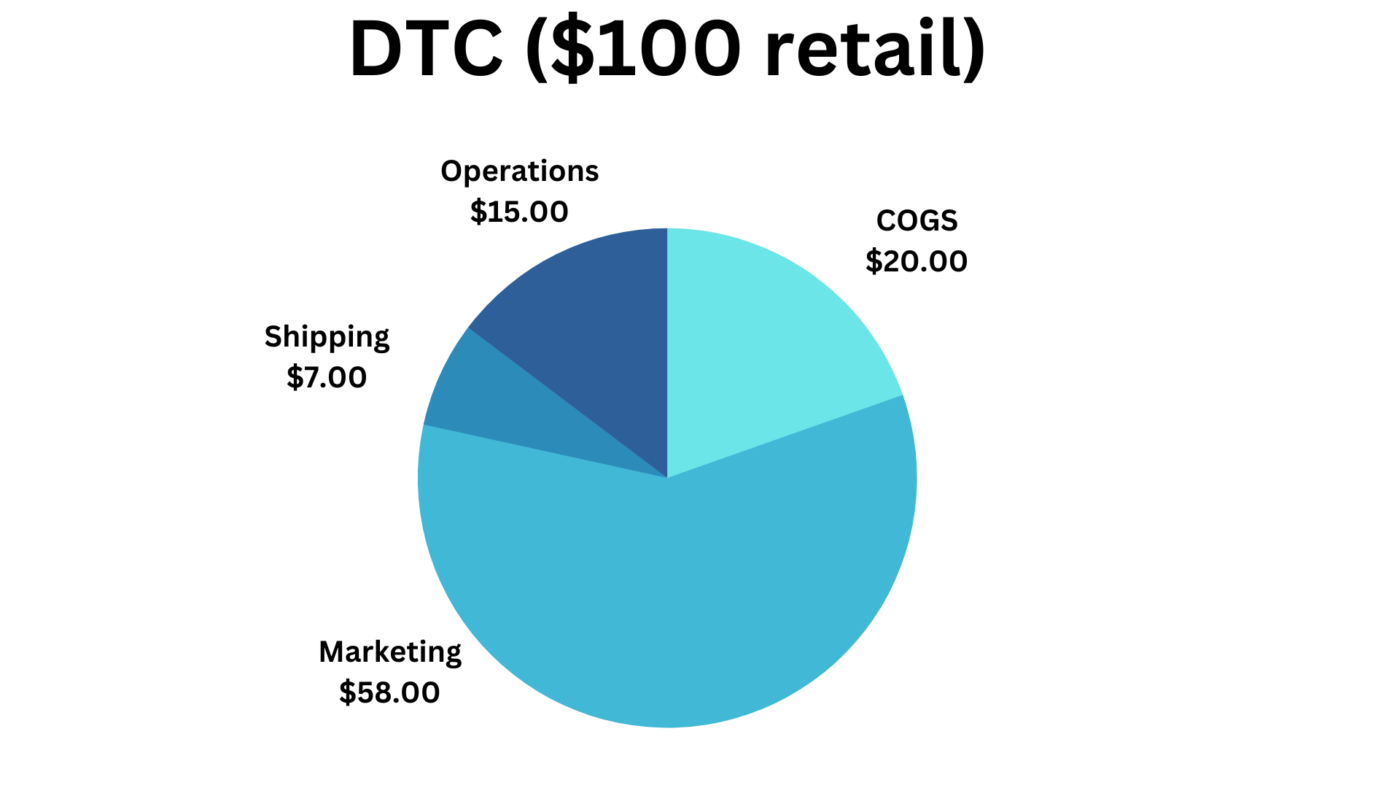

But, don’t forget: without distributors and retailers, the brand has to take on full responsibility for marketing. And, as it turns out, that marketing is expensive.

The New Middleman

Here is a dirty truth about DTC: no middlemen are really eliminated. They are simply replaced by new middlemen named Amazon, Google, and Meta. And, of course, there are also lots of social media influencers.

Shockingly, the new middlemen are at least as expensive as traditional middlemen. In the example above, distributors and retailers are eating up about 59% of the true gross margin. Comparatively, a DTC brand is spending between 55-65% of its revenue on marketing.

That is not good, and to make matters worse, marketing costs are rising every year as DTC matures.

Here is the other hidden cost in DTC that really affects the bottom line: shipping. While it may cost $20 to ship a case of 100 bottles to a traditional retailer, it might cost in the range of $400-$600 to ship those same 100 bottles one at a time directly to consumers.

Obviously, the impact of shipping on DTC efficiency varies based on the product, but a typical guess would be about 7% of revenue.

When you combine the increased marketing costs with the increased shipping costs and you throw in customer service, fulfillment, and a host of other retail-oriented expenses, DTC is suddenly way less efficient. Here is how it might look:

You might notice that something is missing from this pie chart: profit. There is no room for profit.

When DTC brands find themselves in this position, they have only two choices to create a profit: raise the retail price or lower COGS. Both are bad for the consumer, but in today’s price-sensitive market, the trend has been to lower COGS. That is why you are starting to hear DTC gurus talking about driving gross margin up to 90% or even higher.

Getting the gross margin to 90% fixes the profitability problem, but comes with some serious baggage. Suddenly, the DTC brand is selling a $10 COGS product for $100 while competitors outside DTC using more efficient distribution are able to sell a similar product for $50.

Granted, there are usually opportunities to reduce COGS without weakening the product. But once you have exhausted those opportunities, driving down COGS further is probably not a winning strategy because it weakens your product position against competitors.

The same problem exists for raising prices. Yes, every brand should avoid leaving money on the table by pricing too low. But, on the other hand, raising prices simply does not work if you have strong competition taking advantage of more efficient distribution and pricing below you.

Summary

Here are some important points:

- Don’t assume that DTC is the only way or even the best way to get your brand to market. Yes, everyone is doing it, but that does not mean it is for everyone.

- If you are an established brand, think twice about shifting to DTC and cutting out the distributors and retailers that have built your brand for you. They may be more of a bargain than you think.

- If you are a new brand, even if you go DTC, consider pursuing other distribution channels from the beginning.

- Remember that as DTC continues to mature, DTC marketing is likely to become even less efficient. DTC is hard and getting harder.

It is absolutely true that DTC has launched a lot of brands over the past ten years. In some cases, those brands would never have had a chance in traditional distribution. However, that does not mean DTC is best for your brand. Carefully count the costs.